In a previous piece, I gave a high-level description of right-wing populism as it currently exists in 21st century America. This is intended to, in some ways, be a follow up that focuses specifically on the American liberty movement, which I believe experienced a fundamental split in the 20th century.

I want to state up-front that I will be using the terms classical liberal and libertarian in this piece to describe this divide, but I do understand that these are terms whose boundaries are in flux and often disputed. If you object to how I use these terms, that’s fine; I only ask that you grant me my definitions for the duration of the piece so that you can understand the point I am making, even if ultimately you would use different terminology.

That said, by the time you reach the end, I think you’ll understand why I chose to use terminology in the way I did. The individuals that, in my view, represent classical liberals in this rift by and large self-identified as liberals, and the individuals that represent libertarianism self-identified as libertarian.

An Extremely Brief History of Classical Liberalism

One could write entire books on this subject, so I will not go into a lot of detail here. My intent here is to set the stage. For those interested in a more thorough history, I recommend this very good book on the subject.

Until the 20th century, there was no such thing as classical liberalism; there was merely liberalism, which represented the ideas that we now think of as classical liberalism. Liberals strongly favored the republican form of government, representative democracy, checks and balances, equality under the law, capitalism and free trade, and relaxed immigration policy.

This continued into the 20th century, which is where we hit the first major development. The Austrian School of economics, which technically began in the late 19th century, started to exercise its influence on American liberalism through writers like Friedrich Hayek and Ludwig von Mises. They provided new and compelling arguments for why free market economics works as well as it does and why attempts to centrally plan an economy generally fail. They also firmly tied the importance of personal liberty with economic liberty, arguing that one cannot meaningfully have one without the other.

Notably absent from their writing is a concept that anyone who has spent any time around libertarians has likely heard before: the Non-Aggression Principle.

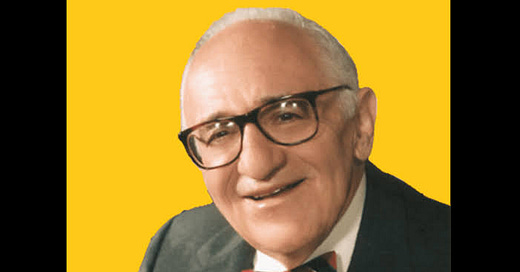

Rothbard’s Moral Turn

Murray Rothbard is the founding father of what we now call libertarianism in the United States. He represents the key point where classical liberalism and libertarianism split.

Rothbard styled himself as a successor to Mises; while he was never taught by Mises in any official capacity, he was heavily influenced by the work of Mises and the two engaged in correspondence. Indeed, the two modern institutions of note bearing the name of Mises, the Mises Institute and the Mises Caucus, would have been named more accurately if they used the name Rothbard instead.

That said, styling yourself as a successor does not make one simply the newest expression of that person’s ideas, and Rothbard deviated from Mises significantly when he created his Non-Aggression Axiom.

The Non-Aggression Axiom, for those unfamiliar, is as follows: the use of force is only permitted in defense of one’s person or justly acquired property. The initiation of force against someone else’s person or justly acquired property is never morally justifiable.

Strictly speaking, Ayn Rand actually invented the concept with her Non-Aggression Principle, and though she defined it more or less the same way Rothbard defined his Non-Aggression Axiom, their arguments in support of this principle, how they interpreted the meaning of the principle, and some of the moral conclusions they drew from it, differed significantly, and it was Rothbard’s vision that primarily drove the libertarian movement going forward.

(One could write at length about how Ayn Rand influenced the liberty movement but that would be outside of the scope of this piece. Her own movement of Objectivism is distinct from libertarianism explicitly and continues to this day.)

Rothbard’s argument for the Non-Aggression Axiom was essentially a modified version of the Kantian categorical imperative. He argued that, if we assume morality exists and moral principles are universal, the only moral principle that everyone could reasonably follow at the same time with no contradiction of behavior was the Non-Aggression Axiom. Note that this is a very brief summary; I would recommend Rothbard’s book The Ethics of Liberty for a complete account of his argument.

This introduced into liberalism something that had not existed before: a moral foundation. Previous liberal thinkers, while not necessarily abstaining from making moral claims, were generally very careful not to make moral assertions when unnecessary. Mises in particular made the case that liberalism cannot tell you what is good in live or the kind of life one should live; only that a liberal society provides the best social means towards almost any end you can imagine.

This is where Ayn Rand’s claim that libertarianism was her ideas “with the teeth pulled out of them” starts to make sense, and Rand used the word libertarianism like I do: to refer to Rothbard’s philosophy and the movement downstream from it.

Whether you agree with its conclusions or not, Ayn Rand’s Objectivism provided a moral foundation that goes much deeper than the Non-Aggression Principle she coined, which she saw as simply one of many moral conclusions that followed from her core principles. In her view, by reshaping it into a Kantian axiom, unmoored from any deeper moral system or set of values, Rothbard has removed crucial context that will result in invalid conclusions.

In this critique, I believe she is correct. From a Rothbardian point of view, the Non-Aggression Axiom is essentially the one and only moral principle and the only heuristic by which behavior can be judged from a moral point of view. In this view, any principles or norms that aren’t about the use of force are conventional rather than moral or ethical.

Rothbard proceeded to ruthlessly apply his one and only moral yardstick to everything he could. He concluded that there was no way to have a government, with its monopoly on the use of force, that was compliant with this moral principle. Naturally, this mean no government was tolerable, and Rothbard coined the term anarcho-capitalism to describe his vision of a society with no government that strictly followed the Non-Aggression Axiom.

(As an aside, I want to avoid confusion and note that another thinker, David D. Friedman, son of famed economist Milton Friedman, has also used anarcho-capitalism to describe a superficially similar point of view. His arguments and foundations are completely different, don’t make reference to non-aggression at all, and don’t even presume that an anarcho-capitalist society would be libertarian. As far as I know, there is not a large movement of Friedmanite anarcho-capitalists, though they do exist.)

Enter Hoppe

Rothbard was a political activist for virtually his entire adult life, and there were many notable twists and turns over the years. Most notable was his so-called paleo turn in the late 80s and early 90s, where he began taking more openly reactionary views on social issues (and race in particular), began his opposition to immigration, and started teaching his successor, Hans-Hermann Hoppe.

Hans-Hermann Hoppe represents the culmination of Rothbard’s foundational premises. Much of the libertarian movement today is Hoppean, though it is often the case that they do not know specifically that Hoppe is the source of these ideas.

Hoppe’s major innovation was to introduce a new concept that, when combined with the Non-Aggression Axiom, actually implies socially conservative views. He did this through the concept of time preference.

In his view, someone with low time preference has the good sense and discipline to forego a good in the present for the sake of something better in the future. Someone with high time preference tends to prefer immediate gratification and has less of an eye toward the future.

He argues that a feedback loop is created as capital accumulates, rewarding more and more low time preference behavior. Any social or cultural move toward a high time preference is seen as degenerate in both the moral and literal sense of the word, as it represents a degeneration of society back toward a more primitive form.

Hoppe envisions an anarcho-capitalist society comprising small-scale private governments, completely voluntary and compliant with the Non-Aggression Axiom. These communities, operating completely privately, are free to set any rules they want, and no aggression is committed since everyone in the community consented to the rules by choosing to live there.

In particular, he is famous for his claim that, in a libertarian social order, such private governments would have to remove people, physically if needed, that promote democracy, homosexuality, or other things Hoppe sees as representing high time preference. Otherwise, society would begin to degenerate and statism would arise.

Having reached these conclusions, Hoppe then uses this framework to analyze the present-day political situation. He argues that, since the US government is tax funded, the country is something of a shared property of taxpayers and operates like a statist version of one of Hoppe’s private governments.

As such, this private government is free to take similar action, such as restricting immigration, in order to support the feedback loop of low time preference.

The Alt-Right Pipeline: Time Preference Without Non-Aggression

It’s not difficult to see how there might be a connection between libertarianism and the far right, given the above. Despite differing premises in other areas, they share similar ideas about the kind of society they want to see realized, and similar moral judgments of others.

Much has been said of the so-called alt-right pipeline, with the most extreme views being that it doesn’t exist at all, or that anyone self-identifying as libertarianism is already on their way to becoming fascist-adjacent.

I will take a middle path here. It exists, but most self-identified libertarians are not libertarians proper but classical liberals. Classical liberals are unlikely to find the alt-right appealing, since unlike libertarians, they do not share a set of social goals, values, and moral judgments with the far right. As such, they almost never go down the pipeline.

For a libertarian, though, it only takes one bit of reasoning to unravel libertarianism completely, leading someone to just become a reactionary social conservative in full. What if a strict adherence to the Non-Aggression Axiom itself enables high time preference behavior, at least in some contexts?

This puts one in a bind where one has to choose between the two. And naturally, if you believe that a functioning society itself depends on low time preference behavior, you’ll choose low time preference over non-aggression.

Once one has made that leap, nothing is left of classical liberalism. One is no longer concerned with liberty or small government, since those conclusions were a product of the Non-Aggression Axiom. One is only concerned with strict enforcement of the correct social values to enable low time preference behavior, and a moral code that demonizes any behavior seen as high time preference or decadent. All else is secondary.

Note: I’m not arguing the above is some inevitable path someone will take. It is more intended as an explanation for why some people end up somewhere seemingly contrary to libertarianism from libertarianism.

The Solution

I’m about to say something that might get me tarred-and-feathered in libertarian circles but hear me out as I explain what I mean.

We need to abandon the Non-Aggression Principle as our core moral principle.

Lest I be misinterpreted, I’m not arguing that there is no utility in the Non-Aggression Principle. To be sure, there is. But it can’t be seen as the one and only true political value, and the end-all be-all of moral reasoning. It should be seen as a useful oversimplification that is broadly true but competes with other values and concerns.

Classical liberals made the case for liberty for hundreds of years without even having the Non-Aggression Principle, so I think we can get by with the less dogmatic version I described above.

Rather than attempting to treat politics like a field of mathematics, where we simply find the correct starting premises and “do the math”, we should treat it as a branch of ethics in the classical sense of the term. Rather than a series of principles, we should ground our ideas in a series of values.

Unlike principles, which are rigid and almost take a life of their own without context, values provide a general guidepost but leave us to reason out the specifics. This enables a lot more evolution of thought and self-correction. In particular, it enables one’s principles, which in this approach are simply downstream of one’s values, to change based on evidence.

I have some ideas for what I think those values should be, but I’ll leave that for another piece.

This is informative. Sounds like you've read a lot by the authors involved?